We need stories and we need numbers.

That’s how we make sense of things. Journalists know this. In newspapers and on the BBC news, we are told that over 40,000 people have died from Covid-19 (so we can see how big it is), and then we are told stories of a young nurse who died, of a father who can’t be visited in his dying days, and of funeral after lonely funeral (so we can see how bad it is, and how heart-breaking).

Sometimes the stories come first. A doctor in Wuhan tells colleagues of a patient with strange new symptoms. Then another doctor tells a similar story. And another. Better start counting. These Wuhan stories were followed by numbers, and then by lockdown and travel bans.

Sometimes the numbers come first. We look at the figures of Covid-19 deaths and see that the very vast majority are elderly people. Better start understanding why, and what the stories are behind those figures. These numbers were followed by letters from the UK government telling over a million people to stay at home for 12 weeks.

Stories plus numbers should lead to action.

Guidance, policies, funding, priorisation, training, support. Numbers and stories show us who needs to be prioritised for testing, for PPE, for support, for funding, for training.

In an emergency like the Covid-19 pandemic, we must not wait for the most complete evidence or a full understanding of what the numbers mean. The best outcomes have been in countries were governments did not wait for the evidence of comprehensive numbers before taking action. Get people off the streets, quick. Get care staff into PPE. You can always relax the rules later, when we know and understand more.

Some of the action has been too slow, and the results are close to catastrophic.

When stories emerged of care home residents dying of suspected Covid-19, with dismal levels of PPE and little guidance for staff, that should be enough to ring the alarm bells. Start counting the numbers, but also, start putting in the right support measures.

That same catastrophe also threatens people with learning disabilities.

It is obvious, by now, that attention must be paid to groups of people who are at disproportionate risk from Covid-19. We have learnt from the numbers and the stories that this includes quite a few groups of people. Elderly, underlying health condition, living together in a group, dependent on close contact with carers: BINGO.

Quite why it took so long to figure out that people in care homes are at risk is beyond me, but at least that awareness is now leading to action, albeit slowly.

So why is no such action apparent when it comes to people with learning disabilities?

Of course not every person with a learning disability is at risk (just as not every 85 year old will succumb to the virus), but overall, they tick quite a few boxes that should ALERT us. If we are to Stay Alert, as we are told we must, I’d quite like to see policy makers Be Alert for starters.

Vulnerabilities

There are some very good reasons for Being Alert. Let me spell it out once again. I hope you are able to skip this next bit because you know it already, but here goes.

People with learning disabilities:

- Are “dying before their time” already. ALERT! We’re talking about people dying roughly 25 years earlier than the general population.

- The most common reasons for dying too soon are:

- Delays or problems with diagnosis or treatment

- Problems with identifying needs and providing appropriate care in response to changing needs

- I want you to read that again. It’s highly relevant to the Covid-19 situation. ALERT!

- Have much higher rates of co-morbidities. That’s “underlying health conditions” in Covid-speak. Think diabetes, heart disease, lung problems. Startling fact: 41% of people with learning disabilities who died in 2018, died of pneumonia or aspiration pneumonia. ALERT!

- Continue to be at risk of unconscious bias, where their lives are not as highly valued. ALERT! Stories abound of families having to fight for their sons, daughters, siblings, to make sure they get the healthcare they need. (What other mother is ever asked “Could you explain what your son means to you?”)

- Often share the same risks as people in care homes:

- they live together with others

- they depend on others to provide physical care, which can’t be done at a 2 metre distance

- they may find it difficult to understand the need for lockdown measures. ALERT! ALERT!

- They face huge barriers to getting equitable hospital care. ALERT! See here for some further thoughts on this.

- Learning disability services are under-prepared and under-supported to meet the needs of a population at risk and in lockdown. ALERT!

We have heard some moving stories from heart-broken families. It’s been on the news and in newspapers. I found Rory Kinnear’s story particularly poignant:

“My sister died of coronavirus. She needed care, but her life was not disposable.”

So, with those stories, and the knowledge we already have of the extreme vulnerability of this population, we need to start taking action.

Testing please

One of the things we must start doing is ensuring that people with learning disabilities, and those who live with them and support them (families, care staff), have speedy access to Covid-19 tests. Tests are now available to care home residents, but (and I quote here from the government website) “at the moment, you can only get tests if your care home looks after older people or people with dementia”.

So, no luck getting hold of tests if you are managing a home for six people with learning disabilities in their 50s, several of whom are rather frail and have already been in and out of hospital with pneumonia. If there is a logic, it eludes me.

Numbers please

Whilst sorting out the support measures, we REALLY need the numbers. As soon as possible, which is as soon as they are available.

The LeDeR programme

The initial pledge from NHS England to publish data on Covid-19 deaths in next year’s annual report of the ongoing national Learning Disability Mortality Review (LeDeR), was just not good enough. It is too late, in 2021, to find out about people with learning disabilities who died of Covid-19 in 2020.

There is a system in England for reporting every single death of a person with learning disabilities, along with the cause of death and several other characteristics (age, gender, etc). This now includes the reporting of confirmed or suspected Covid-19 deaths. They are sent to NHS England every week.

I am really pleased to see that just as I was writing this blog post, NHS England has released these weekly figures. Here they are, hot off the press.

As I said before, we all know that no numbers are perfect. They need to be contextualised. We will need to understand how these numbers compare – with deaths in a similar period last year; with the general population; etc. But it’s a start.

I am more of a story person than a number person – or, in academic jargon, I’m better at qualitative research than quantitative research. Thankfully, there are some outstanding number researchers out there, who have been waving the flag for number crunching. They can explain it much better than I can. I highly recommend Professor Chris Hatton’s blogposts. He, and his colleague Gyles Glover, are the Kings of Numbers, and they can really help us here.

The LeDeR team is brilliant at combining numbers with stories, and I’m sure they will be looking into the details of these Covid-19 deaths.

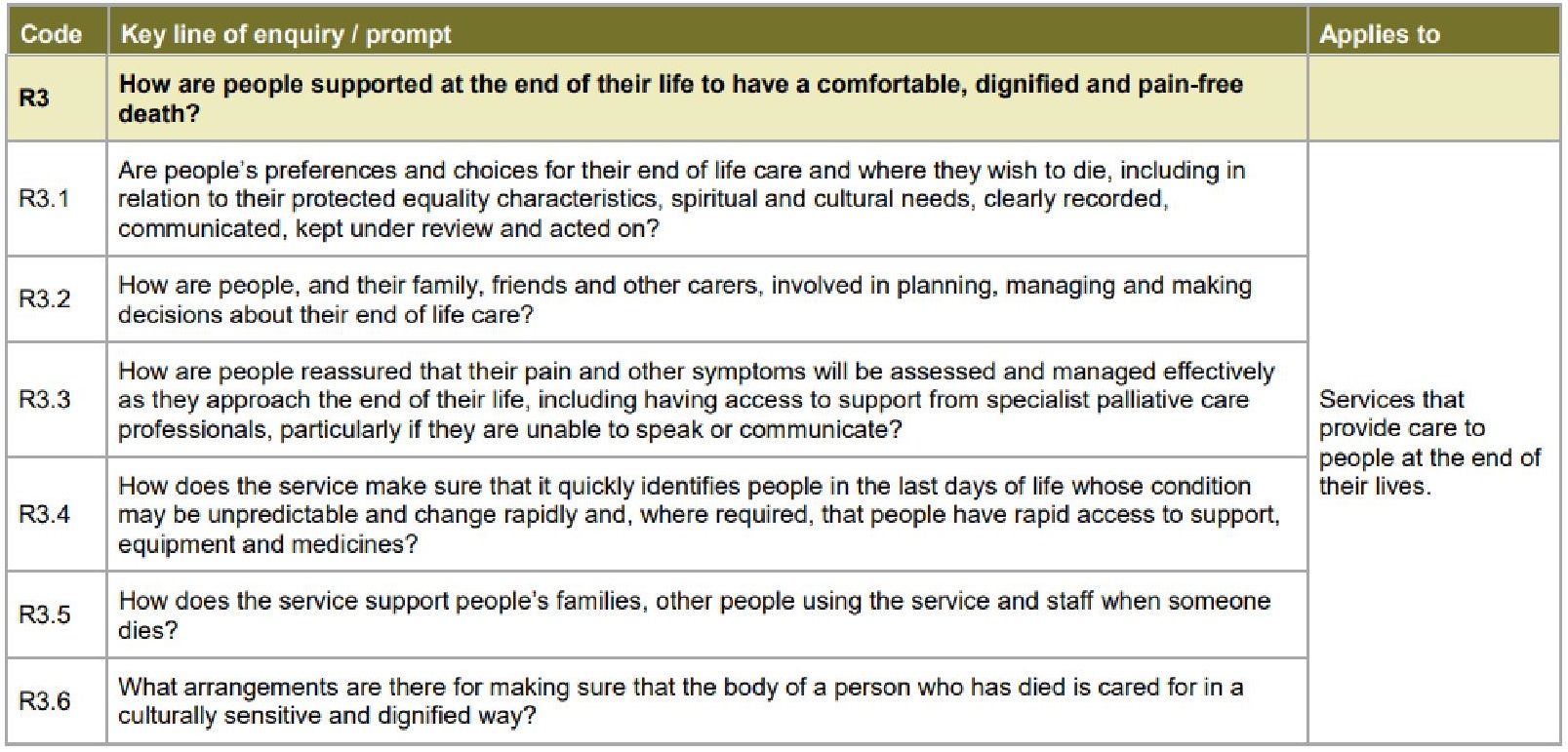

The Care Quality Commission

There have also been pledges from the Care Quality Commission to make available the numbers they’ve got, and to start analysing them properly. Their figures show that deaths in homes where people with learning disabilities may live, were up 175% compared with last year.

I’m not quite sure why releasing this information needed a request from the BBC. Perhaps there is a worry that the figures are taken out of context, or mis-interpreted (indeed the CQC warns against this). But from where I am sitting, it seems that we can do the interpreting as time goes on. Please keep giving us the numbers.

NHS Covid-19 daily deaths

It’s the same with the figures that are now finally being collected and published as part of the reporting on NHS Covid-19 daily deaths. This shows that of all confirmed Covid-19 deaths in hospital, 2% had a learning disability or autism.

At first glance, that looks reasonable. After all, it is estimated that around 2% of the population in England has a learning disability. BUT… read this, from the 2015 report by those Kings of Numbers, Chris Hatton and Gyles Glover (and a few other royals):

Estimates suggest that only 23% of adults with learning disabilities in England are identified as such on GP registers, the most comprehensive identification source within health or social services in England. The remaining 77% have been referred to as the ‘hidden majority’ of adults with learning disabilities who typically remain invisible in data collections.

In short, only about 0.5% of the population in England is known and recorded to have learning disabilities, to the extent that they would show up in the NHS Covid-19 table. Now, I’m absolutely not a Queen of Numbers (and please Kings and Queens of Numbers out there, correct me if I’m wrong), but it sounds to me that “2% of people who died of Covid had a learning disability” is NOT in line with the population figures. It’s at least four times more than I would expect.

Moral of this blog post:

-

Tell the stories.

-

Count the numbers.

-

And as you go along with the counting, SHOW YOUR WORKINGS, so that we can…

-

Start working out what it all means, and

-

Take action, based on all available evidence.

And if any government person is reading this, could I please point you to numbers 2 and 3 of your own advice:

-

STAY ALERT.

-

CONTROL THE VIRUS.

-

SAVE LIVES.

I have Stayed Alert, but I cannot Control The Virus and Save Lives of people with learning disabilities, unless there is action from the top.

(In case you’re worried: This story has a happy ending. My temperature started dropping and after a week in bed, I’m now completely fine. But now we all know what to do, just in case.)

(In case you’re worried: This story has a happy ending. My temperature started dropping and after a week in bed, I’m now completely fine. But now we all know what to do, just in case.)