This blog post is reproduced (with permission) from an article I wrote for PMLD Link, a journal for those supporting people with profound and multiple disabilities. It is a special issue full of stories and articles about death and loss (Winter 2019, Vol 31 No 3 Issue 94).

The death of someone close to us is one of the hardest things we ever have to cope with.

We can never be really prepared, nor can we make the process of grieving quick or easy. It takes years to adjust to a world that doesn’t have the person we love in it. That world can never be the same again.

How much more difficult is this for someone with profound intellectual disabilities? Their world may be utterly shattered by the death of a parent, for example. It’s something most parents of people with disabilities will have thought and worried about for a long, long time. What will happen to him when I am no longer there?

The question is not only a practical one (Who will look after him, and will they do it properly, with love and care?) but also an emotional one (How will he cope with missing me?)

I will share some of the things I’ve learned over the past 35 years of living and working with people with intellectual disabilities, many of whom had to cope with significant bereavements; and of doing research into death, dying, bereavement and intellectual disabilities. I am going to tell you the real-life story of Carlina Pacelli (not her real name), who moved into a community-based home for six people with intellectual disabilities where I was the manager at the time.

Carlina, a woman in her 30s, had profound intellectual disabilities and was a wheelchair user. Until the move, she lived with her parents, who were getting increasingly frail and were struggling to support Carlina. This was a huge transition for the parents as well as Carlina. Her family was close and loving; her parents, brothers and aunts visited often, and she went to see her parents at their home every other week.

Helping Carlina to cope with her parents’ deaths

Five years after the move, Carlina’s father became gravely ill. We could not explain this to Carlina, as she did not understand words at all, and did not use them. The only way to ‘tell’ her was through experience, and through showing her. We took her to visit her father several times in hospital. When he died, the family felt unable to support Carlina, as they were coping with their own strong feelings of grief. How could we help her?

I have always found it quite helpful to think about the tasks of bereavement [1]. These tasks are in no specific order and each one may be revisited or repeated, depending on the needs of the person:

-

Accept the reality of the loss

-

Process the pain of grief

-

Adjust to a world without the person who has died

-

Find an enduring connection with the person who has died

How could Carlina be best helped to understand the bad news of her father’s death? It’s difficult to ‘accept the reality of the loss’ if you don’t know or understand what has happened. It was the first time someone in Carlina’s close family circle had died. Verbal explanations made no sense to her. Staff tried to talk about Dad with a sad facial expression, but Carlina, who was highly sociable and loved people talking to her, was mostly excited and pleased when they did so.

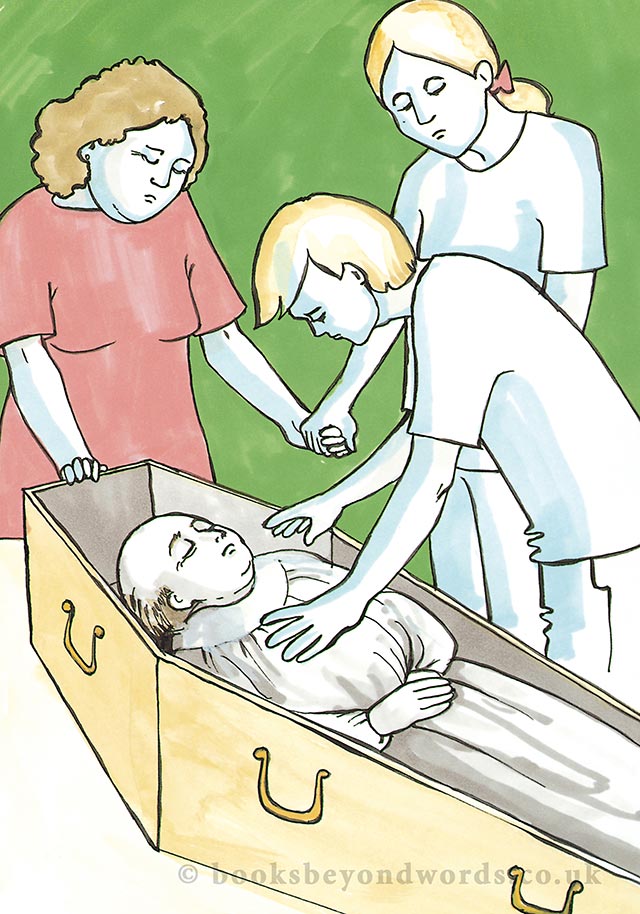

We took Carlina to the chapel of rest so she could see her father’s body in the coffin.

She was initially highly excited about this unusual outing, but when the initial excitement of the outing had subsided, she became very quiet, staring at him. She was helped to stand up from her wheelchair so she could touch her father’s body. She didn’t seem to understand and made it clear that she wanted to leave.

Funerals are important rituals where people with and without intellectual disabilities can share their grief. Even if someone is unable to understand what has happened, they are likely to pick up on atmosphere and emotion. There is nothing wrong, in my view, with sharing tears and distress – rather, the opposite is true! When I go to a funeral and feel sad, it helps me to see that other people are also sad.

Carlina had never been to a funeral before. Unfortunately (I thought), but perhaps understandably, the family not want Carlina to attend her father’s funeral, as they thought that she would not grasp what was happening. They worried that her excited noises at seeing so many familiar faces gathered in one place would upset the family. I tried to explain that we could support Carlina at the funeral so the family didn’t have to, but the family were adamant. In the end, we felt that we could not go against the family’s wishes at such an emotive time. With the family’s agreement Carlina attended the wake, held in the church the night before the funeral, with only immediate family present. She was very excitable at the start of the wake, but became subdued after ten minutes. The atmosphere in the church was quiet and sad.

Over the next few months, we helped her to visit her mother at least once a week.

At first, Carlina seemed surprised that her father’s armchair was empty and she seemed to be searching for him, trying to wheel her chair through the house. Staff also invited Carlina’s mother to visit regularly; these visits were different from before, as her mother would never have visited without her father.

As the weeks went by, Carlina became more withdrawn and often seemed lost in her own world. We think it took her about a year to work out that her life had changed.

When Carlina’s mother died three years later, exactly the same pattern was followed.

Carlina saw her mother’s body at the same chapel of rest; she attended the wake (but not the funeral); she visited her old family home, now empty, one last time before it was sold; and her brothers, rather than her mother, now made the Sunday afternoon visits to the residential home. Carlina was again withdrawn and subdued in mood for about a year. Grief has its own time table. We felt that this time, she was less excitable at the chapel of rest and at the wake, and seemed to grasp the sadness of the situation better.

I told this story in my book How to break bad news to people with intellectual disabilities.

Carlina’s parents died more than 20 years ago. Since then, Carlina has been to a lot of funerals, as many of her fellow residents and friends have died. Earlier this year, we were devastated by the death of Carlina’s housemate Carol, who moved in at the same time as her. They had lived together for 30 years.

I was sitting at Carol’s open coffin, which had been brought into the church the night before the funeral. Friends were coming and going, including people with intellectual disabilities. Some stayed for just a few seconds, others sat for a long time.

Carlina came in and this time, she seemed to understand immediately what this was about. She looked, she was quiet, she seemed sad. She stayed for longer than I had expected, then wheeled herself out.

I think that after all these decades of repeating the same patterns when somebody dies, she now understands death in a way that she couldn’t when her father died.

Explanations do not have to involve words.

The four tasks of mourning

1. Accepting the reality of the loss

Carlina’s story illustrates how she was helped to understand the reality of her parents’ deaths, and later, of the deaths of her friends. Supporting her to visit her mother was a conscious effort to help Carlina see that her father was no longer there.

There were other ways in which we tried to help Carlina understand that Carol had died. We kept Carol’s empty bedroom open, with flowers and photos, for several weeks. Carlina would often wheel herself past that room, hesitate, have a look.

Carol’s room

I think it’s a good idea to try and find ways to let someone with profound intellectual disabilities see for themselves what has changed. Of course, you also need to take the person’s lead; if they indicate that they want to leave, then they should leave. Helping someone understand the reality of a death can take years, but it is important.

2. Processing the pain of grief

I have found that many people try to protect or distract someone with intellectual disabilities from painful emotions. Perhaps this is because we worry that the feelings are overwhelming and will never stop. In my experience, however, most people (including people with intellectual disabilities) will find a balance between expressing distress and ‘getting on’ with life.

Both of these are important. You cannot be in deep distress all of the time, but similarly, you cannot be cheerful all of the time either. People are truly supported by knowing that their sadness is normal, and that it is allowed.

You can help by acknowledging their feelings and by sharing your own emotions about the loss (it’s OK to cry!). Finding ways to remember the person who has died, with all the sadness that may evoke, is also helpful. You could use photos, storytelling, or anything that reminds them of the person – favourite objects, items of clothing, music they liked… anything!

3. Adjust to a world without the person who has died

This is hard. And the bigger the changes, the harder it is to adjust. Most parents will have thought about this (Carlina’s parents did). If the death of a parent happens at the same time as a move into another home, there are so many changes and losses to cope with at the same time. Sometimes this is unavoidable, but it really is worth planning for change.

If the change is unplanned, then try and see if people’s routines or familiar surroundings can be maintained at all. Would it be possible, for example, for the person to stay in the parental home, at least for a while, perhaps with carers moving in? It’s also worth planning for difficult times, such as birthdays and Christmas.

4. Find an enduring connection with the person who has died

People with profound intellectual disabilities need help in accessing memories. I’ve heard some inspirational stories and innovative ideas of helping people with this.

Turning a dead father’s favourite jumper (which still smells of him) into a cushion; the son often cuddles it, and seems comforted by it.

Or how about a group of proactive parents who are audio-recording their voices so that this can be used to ‘talk’ about them after they have died? I think that’s brilliant.

In fact I wish my own mother, who died five years ago, had done the same… I would love to hear her sing the songs of my childhood. Initially, it would have made me sob. But now it would make me smile. Our connections with the people we love do indeed endure beyond death.

And when it comes to grief, really, we all need the same things.

©booksbeyondwords.co.uk When Dad Died

Helpful resources

- Bereavement and Loss Learning Resource Pack (produced by PAMIS) for those supporting bereaved people with profound and multiple intellectual disabilities and their families and carers.

- My website: breaking bad news to people with intellectual disabilities

[1] This is a concept used in bereavement counselling. It comes from J. Worden (2009) Grief counselling and grief therapy (4th edition). London: Routledge

Pingback: Reasonable adjustments for people with intellectual disabilities during the Covid-19 pandemic |

Pingback: L’Arche, Jean Vanier and revelations of abuse: The tasks of mourning |