I visited Michelle last weekend.

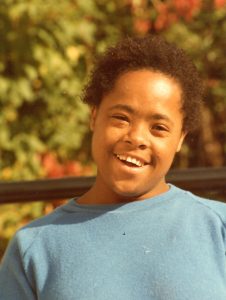

I am somewhat ashamed to say that I hadn’t seen her since her 60th birthday party, which is well over a year ago. My visit was prompted by setting up this website, because I wanted to ask Michelle whether it’s OK to put her photo on my biography page.

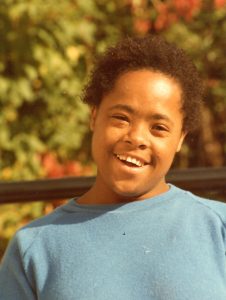

Oh, and how about this one? It’s my favourite. Could I publish that too?

Michelle on her 60th birthday

Michelle was the first long-term friend I made in England.

She was my housemate for almost two years. I had come to the L’Arche community from my family home (via a few years in a student flat) in the Netherlands. Michelle had come to the L’Arche community from a huge institution for the “mentally retarded”, where she had lived from early childhood to young adulthood. I was 21 and she was 29.

The crucial difference between “looking after” people and “being with” people became obvious when I got ill. Suddenly it was me who needed looking after, and it was Michelle who made sure this happened, bringing me hot drinks in the bedroom we shared. We had our disagreements, but being thrown together like that creates a bond that lasts a lifetime.

Michelle serves me my birthday cake, a few weeks after I moved into her home in 1985

So, why hadn’t I seen my friend for so long?

I had followed her trials and tribulations after I moved out of L’Arche. I had visited her in hospital when she developed problems with her brain a few years ago, and we didn’t think she’d make it.

(She did make it. She is made of strong stuff.)

But last year, Michelle moved to a nursing home. It upset me to think of her leaving her home, and I couldn’t face seeing her in what I imagined was an impersonal place with staff who don’t know her.

When people moved out of the large institutions in the 1980s, into small homes in ordinary streets in the community, we told ourselves (and we told them!) that they had found a true home at last.

A home for life.

That was certainly the case in L’Arche, where we tried to create family-like relationships in homes that were warm, welcoming, and above all, ordinary. The house I shared with Michelle was, in my day, home to nine people, four of whom had intellectual disabilities.

But 30 years later, the world is a very different place, and there have been many changes. Along came personal budgets and an emphasis on “choice”. Group living was out; independent living was in.

Many of these changes have been positive, giving people with intellectual disabilities (including many living in L’Arche) an opportunity to live in a place of their own, shared with a friend perhaps. Some people have longed for this. Giving people more choice, more freedom and more control over their lives (including who they live with) is a good thing. It is no longer acceptable for anyone to have to share their bedroom with a stranger from Holland.

Those remaining in larger homes (like Michelle, who never moved out) no longer share their home with assistants in the way we did back then. The stranger from Holland would, nowadays, be like a guest, doing what looks much more like “shift working”. On paper, people like Michelle were now “living independently”, although she still shared her home with three other people with intellectual disabilities. All independent together in the same house.

But here is the problem. All over the UK, there are homes like this, where “independent” people are getting older, needing more care, unable to manage the stairs.

What happens when people reach their twilight years, their sunset?

They live in homes not suited to the needs of old age.

(Picture Victorian London houses. There are no bathrooms downstairs. Nothing is on the same level. There are steps everywhere.)

Their personal budget doesn’t stretch to getting help beyond the basics. Michelle found herself confined to a downstairs room where she sat with just one assistant for much of the time, because she couldn’t get out. She often needed help at night, but there was no “waking staff”.

People racked their brains. Could L’Arche offer her a more suitable house somewhere, with good wheelchair access? Would the local authority increase her funding so that she could be properly supported throughout the day and night?

The answer to both questions was no. The local authority decided that it would be better (read: cheaper) if Michelle moved to a nursing home. So, eventually, and to my great distress, off she went. The only concession was that she was given some extra funding to enable her to visit L’Arche every week, so she could stay in touch with her friends.

I knocked on the door of her new home with some trepidation.

First impressions were not promising. There she was, seated among six other people in wheelchairs in a large and bare lino-floored room, with the oversized TV pumping out jolly music. Several more people milled about in the entrance hall, keeping an eye in case something interesting was happening. (A visitor like me, my piano accordion flung over my shoulder, was certainly interesting.)

Michelle had aged so much in a year that I barely recognised her.

But there is a positive end to this story.

She greeted me with a huge grin. As I went round introducing myself to the people in the room and explaining to them that I was Michelle’s friend, it became obvious that they, too, were her friends. I could see very few members of staff, but those who were there were nothing short of lovely.

We were soon joined by two other friends from L’Arche, who had become part of Michelle’s circle of advocates. We had tea; we looked at photos; we sang Michelle’s favourite songs, courtesy of that accordion (Michelle Ma Belle! Edelweiss! You Are My Sunshine!).

Michelle seemed content. She seemed – dare I say – at home.

Her friend and advocate explained how heartbreaking it had been when Michelle had to move out of the house that had been her home for over 30 years, away from L’Arche and all her friends – but everyone had been pleasantly surprised by how well she had settled. Michelle is an extrovert: she gets her energy from being with people.

Could it be that being surrounded by so many other people, being able to wheel herself to the glass-fronted entrance and keeping an eye on things, is actually better for her than the relative isolation she was forced into by the growing limitations of old age?

Another thought suddenly struck me. Could it be that this place, with its echoing Spartan spaces shared with plenty of other people, actually feels like home, perhaps even comfortingly so, to someone who has spent the first two decades of her life in a large and impersonal institution?

I am reminded of some of the most inspirational nursing homes for people with dementia in the Netherlands, where the décor and even the staff outfits match those of 60 years ago, to make the residents feel that they belong there.

I am seriously challenged by the idea that a woman with Down syndrome who is reaching the end of her life would rather be in a semi-institutional setting than in a cosy home.

Yet if we are to provide truly person-centred support, we need to try and see the world from the other person’s perspective.

Michelle cannot tell us what she wants, but her advocates, who know her well, are clear that she is happy enough in a place where I would absolutely hate to live.

I am not advocating a return to institutional life for people with intellectual disabilities who reach their twilight years. But I am clear that we need to keep an open mind when trying to determine what people’s needs and wishes are, especially people who do not have the ability to tell us.

Dying at home?

I am also reminded of my research into the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities who were dying of cancer, about a decade ago now. I was very surprised to find that “being cared for at home” was not always the preferred option. Some people did not feel safe at home. Others found that their extensive physical needs simply couldn’t be met at home. One woman was clearly confused by the fact that she was both ill and at home: shouldn’t ill people be in hospital?

Three key features of a good place of care were:

- being in safe surroundings with familiar people

- being free of pain and anxiety

- having carers who were well supported

Feeling safe and maintaining bonds with familiar people is probably easiest at home, but it could also be achieved elsewhere.

(If you are interested in the details, I have summarised those findings here.)

L’Arche’s inability to offer Michelle a home during her final years reflects a wider phenomenon. People with intellectual disabilities are ageing.

There is a time bomb ticking away within intellectual disability services.

Many of the homes that were so optimistically set up when the institutions closed in the 1980s and 1990s were designed to help people live independent lives, but they are often utterly unsuited to supporting an elderly population. They are not “future-proof”. The drive towards “independent living” and the slow but sustained cuts in social care funding are also leading to problems when there is a need for increased support.

Where, then, can people with intellectual disabilities call “home” during their final years?

Thankfully, Michelle’s team was able to take some time over finding a suitable nursing home that is close enough to her old home for regular visits. Michelle gets the support she needs to maintain bonds with old friends (often a huge challenge for people who are dependent on others, and on funding, to organise their social life). She is also making new friends.

So I am relieved to find that the nursing home does indeed seem suitable for her. But all too often, there are emergencies. All too often, older people with intellectual disabilities who end up in hospital find that they cannot go back to their old home, because it can no longer accommodate their needs (or perhaps the staff lack the confidence to support those who are ageing and ill – but that’s another story). They are stuck with nowhere to go.

In order to address these issues, may I suggest The Four F’s:

Future proofing people’s homes

Funding

Forward thinking

Flexibility

Now… did Michelle mind having her photo on the internet?

I can’t be totally sure, because the internet is too difficult a concept for someone raised in the pre-digital age. But when I showed her that 60th birthday photo, her eyes lit up with delight: “Me!!”

I take that as a yes. Michelle has always liked being the centre of attention. She even bustled her way up to the altar during our wedding ceremony to join the witnesses, not wanting to miss out on the limelight perhaps.

I hope that she won’t mind me telling you her story.

I hope that she won’t mind me telling you her story.

In my research, I have often had difficulty explaining the need for anonymity to people with intellectual disabilities. Some have protested strongly. People like Michelle have often been anonymous all their lives, unseen, unheard. They deserve their very own place in the limelight.

As her advocate pointed out to me, Michelle has always set great store by “learning”. If she could have chosen a career, she may well have wanted to be a teacher. Through me sharing a bit of her story with you, perhaps she can be a teacher indeed.

So, for good measure, let me throw in this lovely photograph, from way back when I first knew her.

Michelle in 1985

I hope that she won’t mind me telling you her story.

I hope that she won’t mind me telling you her story.