TV deaths

My children can, by now, accurately predict what is coming, every time someone dies in a TV drama. Oh no, not another ridiculous death! I will say, half-amused and half-despairing. This is NOT how people die in real life!

On TV, there will be a few profoundly meaningful last words, spoken with urgency. Look after your mother! I’m sorry for what I did! The killer was Mr… (You never quite catch exactly who the killer was.) Then a bit of a gasp, and the person falls back onto the pillow / slackens in someone’s arms. Dead. There may be a bit of agonising pain thrown in, for effect.

On TV, people go from being fully aware and alive to being fully dead in a matter of seconds. Minutes at most – and that’s stretching it, usually because there is quite a lot of meaningful conversation or painful moaning or heroic resuscitation effort to fit in.

Real deaths

In real life, the space between any last words (meaningful or otherwise) and death is usually hours, days, weeks even. Normal people dying normal deaths just sleep more and more, then slip into semi-consciousness, then leave gaps between breaths, and at some point they simply don’t breathe in again.

TV deaths are, by their very nature, dramatic. Real deaths are usually gentle. They are rarely painful or dramatic.

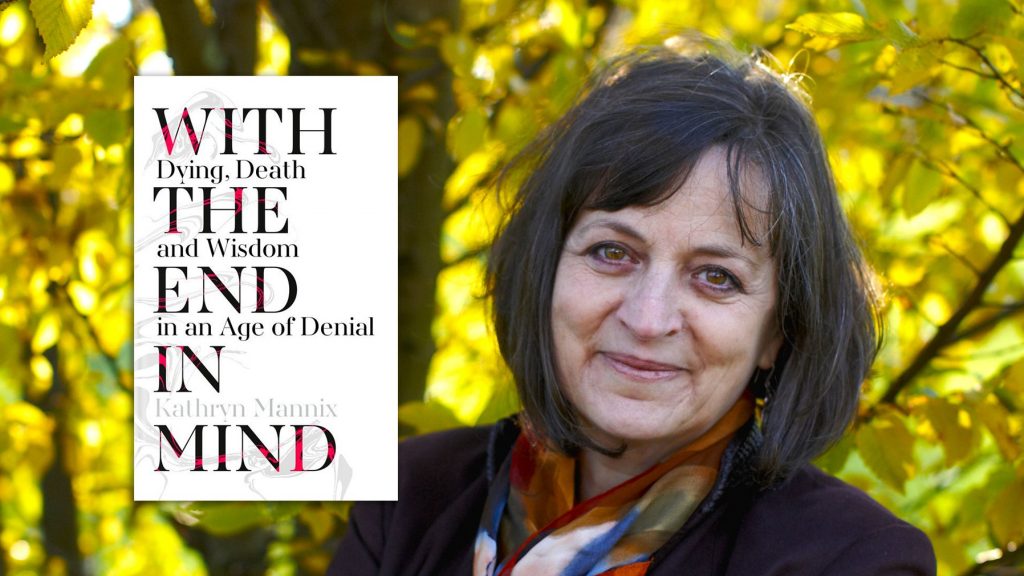

This is beautifully described in With the end in mind: Dying, death and wisdom in an age of denial, an extraordinary book by Kathryn Mannix. She is a pioneering palliative care consultant, and she is on a mission to dispel our fear and ignorance about dying. She does this by telling the stories of the lives and deaths of dozens of her patients.

Here is Sabine. She is nearly eighty.

So starts the first story. And here, indeed, is Sabine, right here in my kitchen, joining me. She drinks her tea black and derides the ‘You call that coffee?’ offered by the beverages trolley. She has a French accent so dense it drapes her speech like an acoustic fog.

I am hooked. This book could be a novel, it is so beautifully written. But it is not a novel. All of it is true, and I recognise all these people. They have been my patients, my neighbours, my friends, my family.

Sabine, for example, is keeping a secret. “She, who wears her Resistance Medal and who withstood the terror of war, is afraid. She knows that widespread bowel cancer has reached her liver and is killing her.”

What follows is an account of how “the leader” at the hospice stuns the author, at the time a young and inexperienced doctor, by explaining to Sabine (and to us) in extraordinary detail what normal dying looks like, and what Sabine can expect .

‘The important thing to notice is that it’s not the same as falling asleep,’ he says. ‘In fact, if you’re well enough to feel you need a nap, then you are well enough to wake up again afterwards. Becoming unconscious doesn’t feel like falling asleep. You won’t even notice it happening.’

He stops and looks at her. She looks at him. I stare at both of them. I think my mouth might be open, and I may even be leaking from my eyes. There is a long silence. Her shoulders relax and she settles against her pillows. She closes her eyes and gives a deep, long sigh, then raises his hand, held in both of hers, shakes it like shaking dice, and gazes at him as she says, simply, ‘Thank you.’ She closes her eyes. We are, it seems, dismissed.

I am also leaking from my eyes. Family, food and sleep all have to be put on hold as more and more people – whole families – keep tumbling out of the pages, joining me and my coffee, and as the night darkens, my wine.

We are no longer familiar with ordinary dying.

Few people have seen the process of dying, the gradual fading, the final breaths. Those of us working in palliative care, who have had the privilege of being alongside hundreds – if not thousands – of dying people, know that there is a pattern that is remarkably similar for most people. This predictable, and usually fairly comfortable, process has traditionally been known and understood by families, who used to watch grandparents, aunts, parents and partners die among them, often in their own beds. But in recent times, deaths have been banished to hospitals, unseen, unknown and frightening.

People with learning disabilities die ordinary deaths, too.

At the end of a talk I gave at a conference last year, someone raised her hand. Is there anything particular we should know about the final days and hours of someone with profound learning disabilities? she wanted to know. I can’t remember what I said – probably something about the need to support the family and care givers, the importance of acknowledging relationships, the recognition of the place of the dying person in everyone’s life, the magnitude of the hole they will leave behind. The questioner looked taken aback.

Is that not what you were expecting to hear? I asked her. She explained that she thought I’d say that someone with learning disabilities might need more pain killers than you or me.

Now it was my turn to be taken aback. I explained that on the contrary, dying is dying! At the end of life, the process of gradually slipping into sleepiness, then unconsciousness, is no different for people with learning disabilities. At the end of life, in the process of dying, equality reigns. It is the social circumstances, the relationships, the support on offer, the access to necessary pain medication (usually no more, but also no less than you or I might need) that can make dying unequal.

Kathryn Mannix’ book is a gift.

I urge you to buy, borrow or beg a copy. It will make you more prepared for dying and more prepared for living. It shows us how ordinary people die, and how we can all embrace life because of it. Because we are all just ordinary people. And that includes people with learning disabilities.

It may not make for gripping TV. But it is rather reassuring.

This is in many ways a reassuring book, and certainly beautifully written. But I think there is a danger that it idealises a certain sort of death, one where there is time for preparation and where Specialist Palliative care services are involved. Can a sudden death be a good death? For whom?

My friend D was sitting on the sofa with her husband, T when he slumped forward, stopped breathing. For a few moments she froze, too panicked even to get to the phone and call 999. He had not been ill, though he had Type 2 diabetes controlled with diet. He had been working as a builder the day before his death though he was in his 70s . He was a fine musician and singer, performing on a Country and Western duo with his wife. An autopsy showed massive coronary artery obstruction. 2 years later D still blames herself for his death. On the other hand I remember another friend A, in her 80s. In the morning she rehearsed with her choir. In the afternoon she went to Quaker meeting and was unexpectedly asked to lead it. After meeting she said that she did not feel terribly well, so one of her friends walked her home, outside the house she vomited, collapsed and died within minutes, again from a massive heart attack. I am not drawing any morals but I think sudden unexpected deaths are very different from the drowsy, sleepy drift into unconsciousness that Kathryn describes so beautifully. Neither of these deaths were over-medicalised, there was no time for that. They occurred at home, among loved ones, but….

You are right Jane, sudden deaths are very different and often much more difficult. What Kathryn’s book describes so beautifully is the process of dying, but of course with sudden deaths there isn’t really much of a process. It is condensed to just minutes or perhaps even seconds. Interestingly, people often say they more afraid of dying than of death itself, and sometimes sudden deaths are described as “a nice way to go” – but I think they are actually much harder, certainly for those left behind. The death of your friend D’s husband sounds particularly traumatic, and there is not much anyone could have done to change that.