Picture this, if you can bear it.

It is the 1980s. A woman in her 50s screams as two strong men hold her down so that a nurse, who is 23 years old, can put a tube into the woman’s nose, all the way down into her stomach. She will be given an artificial feed.

The woman tries everything possible to resist. She doesn’t want to eat.

She hasn’t eaten for months. I don’t think anyone has tried to figure out why not. In any case, the woman never speaks.

This procedure happens twice a day. The place is a very large psychiatric hospital in the Netherlands, on a long-stay ward for the mentally handicapped. The burly men are a senior manager and a strong nursing assistant.

The young nurse is me.

I don’t remember the woman’s name. All I remember is that she had Down Syndrome.

Looking back three decades later, it is blindingly obvious that this was nothing short of ABUSE. If we heard of anything like this happening today, we would demand that the hospital was investigated and the nurse was dragged in front of a disciplinary panel, and possibly struck off the nursing register.

How on earth did I get to that point, the point of not only tolerating but taking part in abusive practice?

I was full of ideals. I had spent almost two years in the L’Arche Community in London, where people with mental handicaps (as it was then called) had become my friends. During my nursing training a few years earlier, I was told that I was paying too much attention to the young men and women in the institution where I was sent for my Mental Handicap Placement – it was a bad idea to become attached, bad for the “patients”, bad for me.

But now, in L’Arche, I had experienced our common humanity: the absolute importance of seeing each other as unique and important individuals.

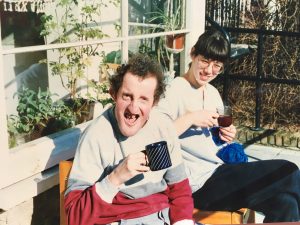

Sharing a cuppa with Keith Lindsay (L’Arche London, 1985)

So, when I went back to the Netherlands and joined a nursing agency, I asked them to send me to work with the mentally handicapped (people weren’t yet called “people” in those days). The experience of not just spending time but sharing time with people with intellectual disabilities had been transformative. I wanted more of it. I wanted to share it with everyone.

I wanted to change the world, so that everyone would know everyone’s value.

It was a culture shock, to say the least, to find that people with intellectual disabilities lived in places that could not be called “home” in any way, shape or form. Where people were lined up naked in the corridor, waiting for their turn in the shower, never mind the builders and repair men walking past. (I was utterly horrified, but what do you do? How do you change it, as a young and unimportant agency nurse?)

It soon became clear that the ward staff, who prided themselves on being a wonderfully tight and supportive team, were supportive of each other, rather than of the people who lived on that ward. Those were not really people. The staff had built walls.

As the new person on shift, I wasn’t aware of those walls at first. I soon found myself on the wrong side (or, as I saw it even then, the right side).

There was the meal, shared around the table with some ten people including myself and another staff member. A particularly nice pudding was communally admired by sending it around the table, everyone taking a bite. Me too, when it was passed to me by the person I was sitting next to. My colleague was horrified, trying to save me from disaster by calling out “No! Don’t eat that, the patients have eaten from it!”

“Then why can’t I?” I said, and took my bite.

(What did she think I might catch? The Mental Handicap Virus?)

Then there was the trip to the swimming pool with the communal changing room. Together with another colleague, I helped three women to change into their costumes. Then I changed into my own. My colleague tried to stop me from the indignity of displaying my birth suit (“The staff changing rooms are over there!”) but I didn’t want to go there: “If they can change in here, then surely so can I?” People’s nakedness would only be undignified, I reckoned, if we made it so, by hiding our own nakedness in the staff changing room.

This was a temporary job. I couldn’t have lasted in that team. I would have been an outcast. It was hard, but my small acts of defiance, of trying to turn patients into people, kept me vaguely sane.

But then came the episode with the woman who was refusing to eat.

This was the real reason they needed an agency nurse. Putting in a nasogastric tube was a job for a trained nurse. It was the one thing I was required to do, which couldn’t be done by anyone else, because there were no other trained nurses on that ward. Articifial feeding was necessary, important, part of the plan for this woman. I wasn’t asked to do it; I was told to do it. By the most senior manager, no less, who came out of his office specifically to assist with the unpleasant task. Refusing to do this would mean I’d lose that job, and not only that, but my nursing agency would have been told that I was no good. End of career.

I didn’t think any of that through, though. I simply went with the flow. I did what was expected. I did as I was told. Clearly, everyone thought this was OK, so who was I to dispute it?

But coming home from those shifts, I cried and cried.

Day after day, I cried. It just didn’t seem right. I was devastated that the woman had to be treated in this way. There was no-one I could talk to about this. I probably couldn’t even explain why I thought it was all wrong. Weren’t we helping to keep this woman alive, by feeding her? What was the problem?

I was perhaps even more devastated that I couldn’t save the world. I thought I could live my ideals, living and working in a way that I knew was right, anywhere. But I found that I couldn’t. Faced with an overwhelmingly large institution, where staff were utterly institutionalised and patients were dehumanised, I had two options:

- Let my ideals go, and become part of the system

- Leave

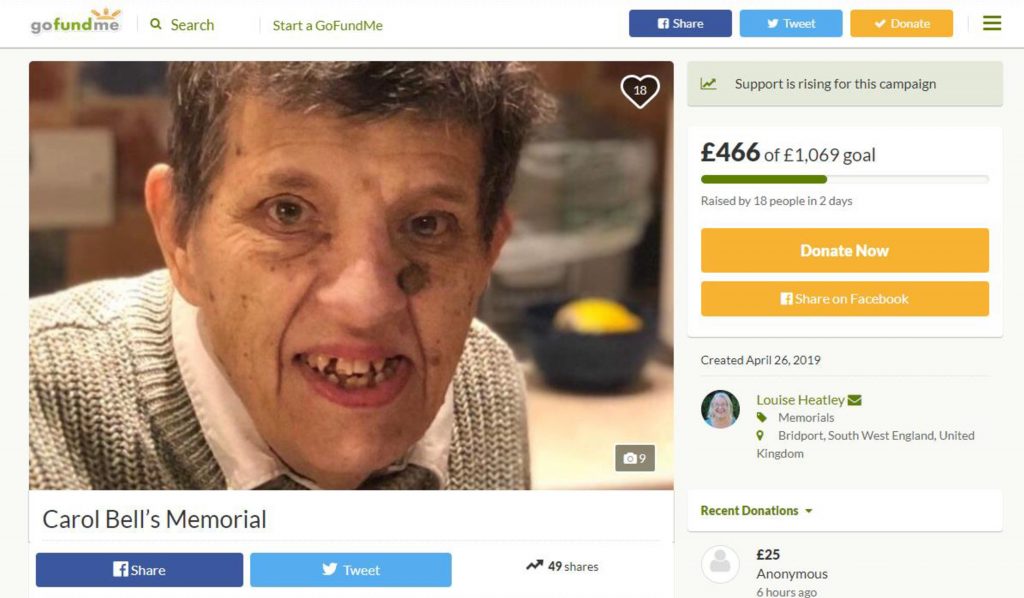

Readers, I left. Around that time, someone from L’Arche London telephoned me. The new home they had been renovating would soon be ready to welcome its first residents, and would I be interested in becoming House Leader? I didn’t need to think about it. I said yes on the spot. Some months later, I moved back to London and started visiting insitutions, just like the Dutch one I had escaped, to meet the people who would become our first residents. Including Carol Bell, who had grown up in such an institution. She was part of the (hopefully) last generation of men and women living their childhood and adulthood as patients rather than as people.

The reason I’m telling you all this now is that I have just forced myself to watch an old documentary about St Lawrence’s Hospital.

This is one of the asylums where society sent its “inadequates”. This is where Keith Lindsay grew up (the wonderful Keith – see photo above): I spotted him 44 seconds into the documentary. I knew it was a grim film to watch, but I didn’t realise quite how grim. Many of the people I’ve known have grown up here, or in similar places. They were profoundly deprived as children, utterly starved of attention and stimulation. It’s horrific. Carol and Michelle and Keith and so many other friends were, truly, survivors.

This film shows how horrid life was for the patients, but also for the staff, who needed to dissociate themselves completely in order to be able to cope. It’s a culture that turned nursing staff into zoo-keepers.

If you can bear it, do watch this film. It was filmed in 1981. That is very recent history. It is living memory. This is what our society thought we should do with people like Keith and Carol and Michelle.

We have come a long, long way, but we cannot be complacent.

Cultures and deep-seated attitudes are not easily changed, and still linger, as the alarmingly recent Winterbourne View scandal has shown. Cheer on the whistle-blowers, the campaigners, the quiet humanisers. I wish I’d been one of those whistle-blowers at the age of 23. I wish I could have done something better for that woman who was refusing to eat.

I couldn’t help her, but she certainly helped me. She was my turning point, the person who made me realise that I had to live my life differently. Sending me back to England, to be welcomed again by Michelle and Keith and other friends in L’Arche; and in turn, to welcome Carol. It is a tribute to the power of their human spirit that they not only survived the decades of deprivation, but thrived.

So thank you, woman-who-refused-to eat. I just wish I could remember your name.

PS those of you who have followed Carol’s story, and seen her obituary in the Guardian, might like to know about the effort to raise funds for a crematorium plot and simple memorial at the local cemetery where her many friends can remember and mourn her. See here.