What does good end of life care planning look like?

What should you talk about and when should you talk about it? Big questions. As I have discussed in my previous blogs, it’s hard enough for any of us to plan for our time of declining health and dying. Much harder, still, for people with learning disabilities.

There is a danger that we talk about it at an unhelpful time or in an unhelpful way. This danger is greatest if there is a tick-box approach to “End Of Life Care Planning”, where the focus is on completed paperwork rather than on communication – something the Royal College of Physicians and other national organisations have been warning against for years.

Nightmare scenario 1

(fictional but based on real life, alas)

George, a healthy 28 year old, moves out of the family home and into supported living (a group home) for the first time. He has autism and moderate learning disabilities. In his first week there, the manager sits down with him and his mother and asks them, pen poised, “What are George’s wishes for end of life care? Would he like to die here, or at home, or in a hospice? And would he like to be resuscitated, yes or no?” The question comes out of the blue. George is terrified. His mother is deeply distressed.

But the other danger is that we don’t talk about it at all.

Nightmare scenario 2

(also fictional; also based on real life)

Fred, an increasingly frail 58 year old with severe learning disabilities, also lives in a group home. He is close to his sisters, who visit often. Over the past year, he has had several chest infections. Each time he recovers, but is weaker and less able to do the things he likes. He can no longer feed himself or walk independently, and his seizures have also increased. His sisters are convinced that he is in considerable pain but the care staff are reluctant to give pain medication, as they feel it makes him drowsy. The care staff want him to maintain his hard-won independence, so they encourage him to keep trying to walk. When Fred goes into hospital with yet another chest infection, the home manager says they cannot have him back until he is better; currently, his physical needs are too great. There is nowhere else to discharge him to, so Fred stays in hospital whilst his sisters try and find a suitable nursing home. He dies in hospital two weeks later, alone and probably terrified. His sisters are deeply distressed but not surprised. His care staff are shocked – they hadn’t expected Fred to die.

So, how should we approach end of life care planning?

Let me talk you through my top tips.

I have to stress that I haven’t tested my tips or asked what families, carers and people with learning disabilities think about them. (If you’d like to do this, I would be delighted!) This blog is based on what I’ve learned from my clinical and research experience, and from reading other people’s stories, guidelines and tips. First of all:

What is end of life care planning?

In a nutshell, it is planning ahead for the last year, months or weeks of life so that there are as few surprises as possible; everyone is prepared for what might happen; and the care someone gets is based on their values and preferences.

I’m calling it end of life care planning because then everyone knows what we’re talking about, but you may also hear the term Advance Care Planning. This is a wider term and includes three things (I’m talking about the UK here – it might be different if you live elsewhere):

- What you want to happen. These are statements about the person’s goals of care, and their personal values. It could be about medical treatment (“I want to be fed by tube if I can’t swallow anymore”) or about place of care (“I don’t want to go into hospital”) or about social aspects of care (“I only drink coffee out of my red mug” and “George is my best friend and I want him to visit me”). These can be recorded, or they can just be discussed. They are NOT legally binding – although any decisions (including best interest decisions) should take them into account.

- What you don’t want to happen. This is also known as Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT). It is a legally binding statement about specific medical interventions that you don’t want. This is where resuscitation statements come in (e.g. DNACPR).

- Who will speak for you. This is also a legal document, appointing a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). This is useful for people who have capacity. They can nominate a person to speak on their behalf, once they lose capacity.

If you want to find out more, there are lots of helpful websites and other resources, e.g. here and here.

When should you start discussions about end of life care planning?

Bearing in mind that you want to be prepared for the worst even when you are hoping for the best, there are some specific situations that should trigger discussion. Here’s a list.

-

The person, or their family, starts the conversation. (Pick up the clues! Create opportunities for discussion, e.g. when famous people, people in soaps on TV, or friends/family are dying)

-

There is a new diagnosis of a progressive life limiting illness, or a new episode of an existing life limiting illness. (Many people with learning disabilities also have life limiting conditions, e.g. tuberous sclerosis. Make sure you review their situation regularly. Is there a change? Would you be surprised if they died within the next 12 months? If not, start the conversation: “What if…”)

-

They have a diagnosis of a condition with a predictable trajectory, which is likely to result in a (further) loss of capacity, such as dementia. (It’s important to make sure that you know what the person’s values and wishes are, before they lose capacity to make this clear.)

-

A change or deterioration in condition.

-

Frequent hospitalisations. (See Fred’s chest infections – they should have triggered “What if…” discussions)

-

A change in a patient’s personal circumstances, such as moving into a care home or the death of a family member. (But be sensitive… see below my further thoughts on George)

-

Routine clinical review of the patient, such as annual reviews.

-

When the previously agreed review interval has finished.

-

The answer to the Surprise Question is “no”. (“Would you be surprised if this person were to die in the next 12 months?”)

Of course it is possible, and perhaps even desirable, to give everyone (regardless how young or healthy they are) an opportunity to start these discussions. They key is that they are sensitive discussions and they respect people’s values.

In the example of George, where the home manager wanted to be prepared for all eventualities (I’m giving him the benefit of the doubt, and won’t assume that he simply wanted to complete his tick box exercise), a better way of approaching the issue might have been:

George, we’re delighted that you are living with us now. Some people want to live in this home for the rest of their lives, and if that’s what they want, we try to make that possible. We hope that you live for a very long time, but here’s a question we ask everyone… If the worst were to happen and you got very ill, or you were going to die, what would you want us to do? Do you think you might want to stay here, or be back with your family perhaps? It’s not something you need to decide now, but if we need to make such big decisions, who should we talk to? Who would help you decide?

It might still not be appropriate to ask George this (and, as the CQC confirmed, there is no actual requirement to do so), but with sensitivity and in the right context, it might help both George and his family to know that his new carers are supportive and able to listen, and think ahead with realism.

What should end of life care discussions be about?

I’ve said it before, and I’m saying it again.

End of life care planning is not so much a question of where and how do you want to DIE? but where and how do you want to LIVE until you die?

This is not so much to do with OUTCOMES (Did he die in the place he said he wanted? TICK! Did he record his funeral wishes? TICK! Was he free of pain? TICK!). Targets like these may have their place, but they can have an adverse effect, if we focus on the targets rather than the person.

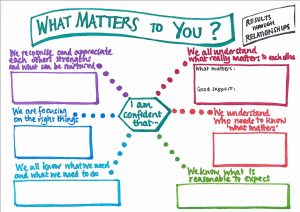

I really like the following ideas, which I have stolen from Saskie Dorman and her colleagues from Dorset End of Life Care Partnership (with permission – thank you Saskie!). Rather than talk about TARGETS, they talk about the CORE CAPABILITIES needed by health and social care staff to improve end of life care support for everyone.

What do we need to be really good at, consistently, to make sure that everyone has as good an experience as possible in the last year of their life? THIS:

-

We recognise when you may be in the last months of your life.

-

We all understand what really matters to you and your family, and focus on this together.

-

You are supported to live well in your own way, as part of your community, finding moments of joy where possible.

-

You are supported to anticipate what may happen towards the end of your life.

-

Your wishes are shared as appropriate (with your consent) so that you are supported through times of illness in a way which feels right to you.

-

You are as comfortable as you want to be, including in the last days of your life.

-

Those close to you feel supported, including after your death.

Taken from: https://whatmattersdorset.org/projects

Your end of life care planning discussions should help you to achieve all of these.

If you are a manager in any service that may support someone with learning disabilities at the end of life, ask yourself: Would we be able to do all of the above? Consistently? If not, what do we need to do to improve?

Doing this well needs a diverse team. Doctors may be better than care staff at recognising the last months of life, or anticipating what may happen. Those closed to the person will understand what matters most to them. Care staff are well placed to help people live in the way they want, even in declining health.

So, don’t worry too much about these questions…

- Where would you like to die?

- What kind of funeral would you like?

Instead, start asking really specific questions, tailored to the person’s situation. Like these…

- Now that you only have 2 hours of energy per day, what would you like to spend it on? (Fred might have chosen to spend it on quality time with his sisters, rather than attempting to walk.)

- When you can’t manage the stairs anymore, would you rather stay in your upstairs bedroom all the time (and have your meals there, and your visitors, but never go out), or would you prefer to move somewhere else with a bedroom on the ground floor, or a lift, so you can still go outside in a wheelchair? (Quite hard if there is no option of a downstairs bedroom in someone’s current home, but it’s a situation I’ve come across more than once. Plan ahead!)

Good luck everyone!

A really useful contribution to discussion. There is more than one way of getting it wrong! I like the idea of the two nightmare scenarios. As you know we did a study of the deaths of people living in supported living or care homes for adults with learning disabilities. We found that a third of even people who had died suddenly, who nobody was expecting to die, had an end of life care plan. I do not know what was in those plans. Probably not the detail of the care the person wanted as they approached the end of their lives. It was not usual for the person themselves to have been involved in drawing up the plan. People who died after an illness that staff realised might lead to death were more likely to have a plan, and to have been involved in making it. Talking about dying does not make it happen. We can’t entirely protect the people we love from death or bereavement, whether they have learning disabilities or not. So your tips make sense to me. People are right to be afraid that people with learning disabilities may not get the healthcare they need, or want. That they may be subjected to healthcare interventions they do not want or need. One way, it seems to me to make that nightmare less likely is to make space to talk about it.