This blog post was first published by Marie Curie, see here.

Some of the challenges people with learning disabilities face when it comes to death and dying are hard to fix, but it seems to me that some solutions are outrageously obvious. Talking openly to people about death, and involving them in everything – including shared rituals of grieving – is one of them.

My friend Pete, who was terrified of death

Let me share the story of a good friend of mine. I’ll call him Pete. Pete had severe learning disabilities and he was terrified of death – perhaps because he watched his father die a painful death at home when he was a child. Or perhaps because when his mother died, Pete was on holiday. He wasn’t told that his mother had died until well after the funeral. Pete came back from holiday and found himself having to move, completely unexpectedly, to a residential home full of strangers.

Pete’s mother died decades ago. I keep hoping that Pete’s story is a history, but sometimes I still hear similar stories of exclusion.

A conspiracy of silence

When I was a hospice nurse in the 1990s, many of my patients had adult sons or daughters with learning disabilities, yet they rarely visited. My suggestion that they should was often met with alarm. Like Pete, many of the relatives with learning disabilities had not been told that their parent was ill, and certainly not that they were expected to die.

“She couldn’t possibly understand!” people would say. Or, “I don’t know how to tell her.” Or, “It will only upset him. What’s the point of doing that?”

Later, when I started doing research into all this, my co-researcher Gary Butler (who has learning disabilities himself) used to get particularly angry about this. “Of course he is going to be upset!” he’d say. “His father is going to die! Why aren’t we allowed to be upset?”

He’d go on to explain, “I know why. It’s because people don’t know how to cope when people with learning disabilities are upset.”

What should we be doing?

But talking openly about death and dying with people with learning disabilities is important. Most people cope best with difficult changes in their lives if they have some way of preparing for it, and if they are helped to understand what is happening. This includes telling people that someone close to them is likely to die, because otherwise, the death will be experienced as an unexpected, sudden death – which is much harder to cope with. Knowing that a loved one is going to die is sad, but sadness is not, in itself, a good enough reason to withhold such knowledge.

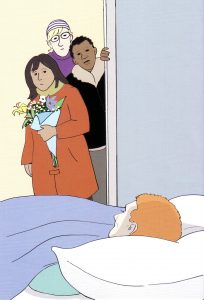

Picture taken from Books Beyond Words: “Am I going to die?”

How to talk about death and dying with people with learning disabilities

- Use simple words. Most people with learning disabilities I have spoken to about this, tell me that the best word to describe death is “DEAD”.

- You can also use the person’s own vocabulary about death. Just make sure it’s their jargon, not yours.

- Check with them what they think those words mean. If someone says “Mum’s gone to heaven”, ask what they think heaven is. It’s also worth checking their understanding of death. Do they think mum will ever come back from heaven?

- Beware of euphemisms! “We lost dad” (why don’t we go looking for him then?). “He has gone to a better place” (Sounds nice. Why can’t I go there too?). One man I knew was excited about going to Devon for a holiday, as he thought it would be a chance to meet his friend who, he’d been told, had “gone to heaven”. A classic case of mishearing the words.

- Some people don’t cope well with uncertainties (such as not knowing exactly when the person is going to die). This is particularly true for people with autism spectrum disorders. Think carefully about how to talk with them about what will happen in the future. It may help, for example, to go through a script (“We don’t know when Dad will die, but when he does, this and this and this will happen”). This can help in preparing someone to cope with what will be an upsetting time.

- Talking is not the only way to explain what is happening. Visiting the ill person or, better still, involving the person with learning disabilities in caring for that person, can be extremely helpful. It can also give comfort after the death.

- Remember that many people with learning disabilities will not initiate conversations about death, but that doesn’t mean they don’t want to talk about it. You can help by talking about the ill or deceased person in day-to-day conversation, helping people to share memories, etc.

Have a go. In the words of one of my advisors with learning disabilities:

“Tell the person the truth. Even if it’s bad news. Don’t be frightened!”

If you want more tips and advice, visit my website on How to break bad news to people with intellectual disabilities.

This is so helpful. A person with intellectual disability does understand but one needs time and patience. This had me thinking. Last year three of the service users who attended my daughter’s day centre left for various reasons. These were her friends and she misses them very much.

Everyday when I go to collect her (even today) the conversation starts with ‘I want Thomas back. Kathy, Luke and Thomas has left. Too bad.

The ‘too bad’ is the response of the carers.

I explained to her and I do this everyday that Thomas left because of money, Kathy left because her family moved home and Luke left because he went to another day centre. Then I say but you have Francis (new service user) and you need to help him because he is new. Once this conversation has taken place she is happy and she will ask me several times during the journey if I am ‘ok’. That is more thoughtful than any of the other siblings.

A few months ago when she asked for her friends I asked her ‘What did I tell you?’ and she repeated exactly what we discussed. So I likened it to bereavement because sometimes she will say that she is sad. She will most certainly be having this conversation throughout next year.

Last week she asked if she could take a Christmas bag with sweets/biscuits for Thomas and today she asked if she could visit Francis at his home. I explained that Francis’s parents may not be able to cope but I said that you could ask his dad. She replied ‘You could do that’.