“I am a man with a learning difficulty. When I was about five or six, the headmaster at my school said that I couldn’t be taught.”

Now here is Richard a few days ago, the man who couldn’t be taught, having successfully completed our 8 week “How to do research” course for people with learning disabilities. At a university, no less. (Yes, he said, do put my picture on the internet.)

Ten students had come faithfully for two hours every week. We were blown away by their commitment, enthusiasm, questions and ideas. There were lots of punch-the-air-in-triumph moments over these past few months. For me, one of those was when a student said exactly this:

“I found that my hypothesis was wrong.”

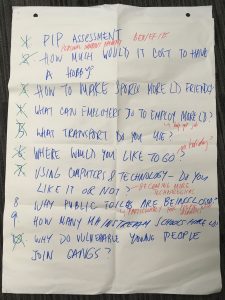

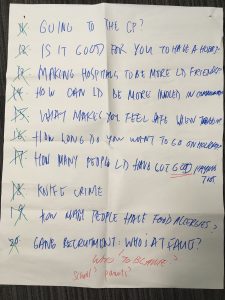

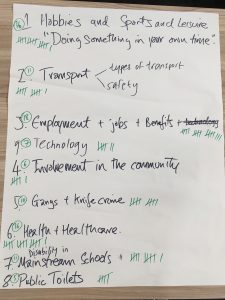

Now that’s a result. The students had come up with their very own research questions. Here’s the long list:

And, following a process of voting by the students, the winning topic was “Employment, jobs and benefits”.

Their research question boiled down to this:

“Why don’t more people with learning disabilities have good paid jobs?”

So, we split the students into three groups, each focusing on a different methodology. Three students worked on a questionnaire, to be handed out to their fellow students. None of these three students had paid jobs, so they worked out questions about this. To their surprise, they found that most of the respondents did have a paid job. Hence the student’s observation that his hypothesis (“People with learning disabilities don’t have paid jobs”) was wrong.

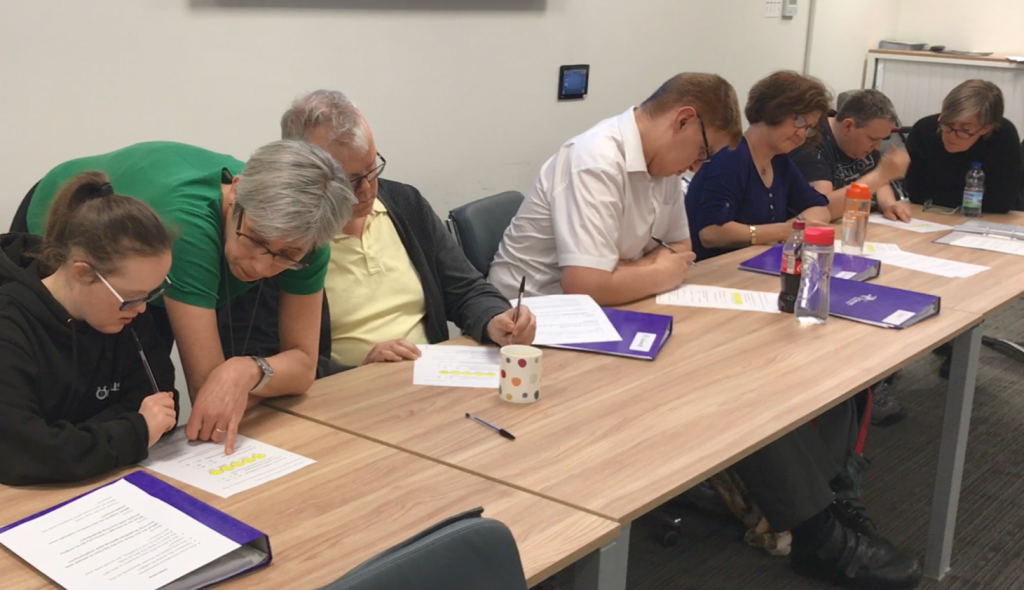

The students fill in the questionnaire

Another group of students worked on doing a one-to-one interview. They selected me as their participant. Their questions were brilliant (“What does this university do to support the employment of people with learning disabilities?”). Their interview skills were pretty good too, considering they’d only had a few hours to plan and practice.

Three students hold a face-to-face interview

(“Irene couldn’t really answer our question,” one student explained to her family afterwards. “Because they don’t employ people with learning disabilities at the moment.” Indeed we don’t. All my research funding applications over the past few years, that have included paid co-researchers, have failed.)

The third group of students worked on planning and facilitating a focus group. They, too, wanted the participants to be people with the power to decide whether to employ people with learning disabilities. Three of us (myself, a tutor and one of the students’ support workers) took part. Again, amazingly good questions, facilitating an excellent group discussion. (“What do you think makes a good employee? What stops you employing people with learning disabilities?”).

Three students facilitate a focus group

This course was an experiment.

I’ve wanted to do it for years. I’ve worked with people with learning disabilities as research advisors and co-researchers. It took me an entire decade to learn how they can truly contribute to and improve our studies, and what adjustments we had to make to ensure they can participate in a meaningful way. Research funders now require “user involvement” in research, but there is little guidance on how to make this happen in practice. Too often, the way we do research remains unchanged, with the Advisors With Learning Disabilities simply sitting in meetings that mostly go over their heads. As one of our contributors once said:

I don’t want to be there just because you want bums on seats.

I have gone a step further and worked with people with learning disabilities as co-facilitators of focus groups. We’ve also had co-researchers with learning disabilities help us interpret the data. But this takes time, and what we never had time for was to teach people properly. I, and most of my research colleagues, have had years of research training; but we somehow expect people with learning disabilities to join us and contribute, without any training at all.

How on earth are they supposed to know what research is?

What is the difference between a Research Question and any old question? What research methods to you choose, and why? What are the difficulties and the possibilities with each method? What makes a good interviewer? What do you need to think about when you run a focus group? What is the difference between open questions and closed questions, and when or why would you use them? How do you make sense of data?

I wondered whether we could really teach those skills. I wondered whether anyone was interested.

We applied for a small amount of grant funding from the NIHR Clinical Research Network, and received £3,000. This just about paid for Claire, my excellent research assistant, to prepare and deliver the course. I threw in my time for free, and two colleagues came to help out for a couple of the sessions. It enabled us to run the course free of charge for students. We reckoned we could accommodate ten students. We’d run it as a trial course.

Where to find these students? Would anyone be interested? I tweeted the information once and was inundated with interested people and organisations. In the end, we had 25 applications and selected 10 students at random. I had not foreseen the heartbreak for people who didn’t get in. One unsuccessful applicant telephoned me within minutes of receiving the email, telling me how hard it is to be always, always turned down for things.

I also hadn’t foreseen how much it would mean to the selected students, who (as we heard from Richard) have often been told that they were no good at school, to come to a university. My sister goes to university, one of them explained. And now I’m going too.

We treated them seriously, and they rose to it. Their confidence soared. Even the very-very-shy student stood up and spoke at the final session this week, presenting their work to family, friends and colleagues. Afterwards, their families and support workers told us that at home and in their jobs, too, their confidence had rocketed. For some students, who work for Mencap, it has already led to new research-related duties at work.

The students always arrived early, homework done, eager to start. And they were simply fabulous. Every week, I’ve been suprised by their insights and their ability to grasp quite complex concepts.

And we’ve had such fun!

They wept with laughter at the session on “Interview Skills” (and, more importantly, they remembered and incorporated those skills when they conducted their own interviews a few weeks later). Claire and I had role-played a very bad research interview, and got the students to hit a buzzer (making rude animal noises) every time they had a tip for me on how to improve my interview skills. Without us telling them anything about what makes a good interviewer, they came up with a pretty comprehensive list (all in the space of 15 minutes):

- Eye contact!

- Don’t talk about yourself all the time!

- You’re putting words into her mouth!

- Don’t look at your watch, or your phone!

- This is not about you, it’s about her! If you make yourself look so important, it makes her feel bad!

- If you’re asking a sensitive question, you have to explain why!

We filmed that session – you can watch it here.

What strikes me, watching it again, is that every single student contributes something useful at some point, from the most vocal to the most shy. For those students to tell me that I’m pretty rubbish and should do better, had the added benefit of giving them confidence that they can talk to a Learned Professor, and even correct her.

We sent them home that week with the instruction to hold a five minute interview with someone (on the same topic as our role play) and then come back to us with a list of Suggestions for Interviewers.

No need for us to write the Research Handbook. The students wrote it themselves.

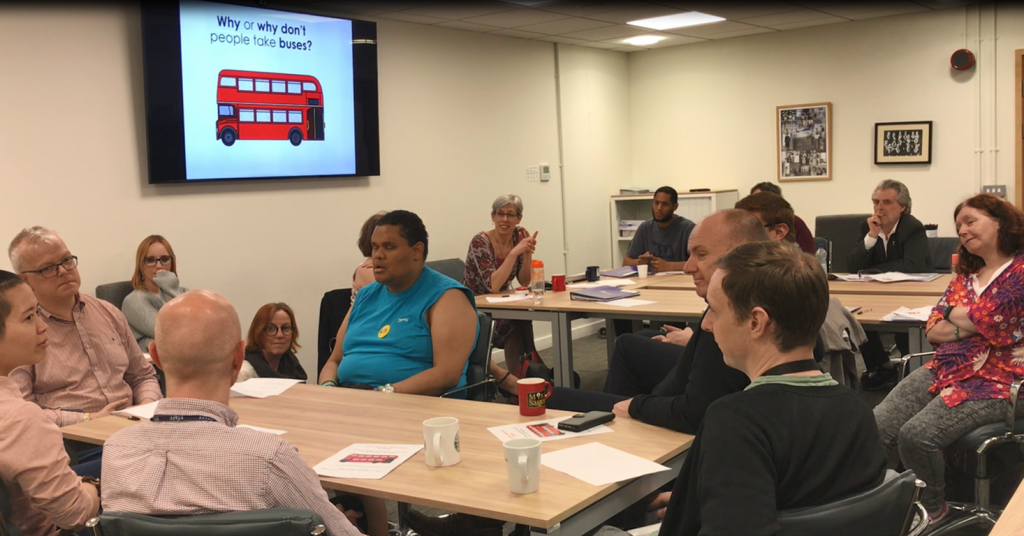

Similarly, the focus group week was impressive and fun. We’d grabbed a couple of colleagues in the office, to form a focus group for the students to practice on. (Our brief was that they’d been commissioned by a bus company to answer this research question: “Why do or don’t people take buses?”) The students soon discovered that facilitating a good discussion, where everyone contributes, is hard work. They noticed that one of the focus group participants talked too much about irrelevant stuff, whilst another said nothing. They took it in turns to try and do something about that.

(We’d been a bit sneaky, briefing our colleagues beforehand to give the students these challenges.)

Two of the students practice running a focus group, with the rest of us observing (and students taking over the “interviewer hot seat” if they had a suggestion for improvement)

The course finished this week. So what’s next?

I have already received enquiries from researchers who need people with learning disabilities to be co-researchers or advisors on projects they are planning. Would our students be able to do this? (Most students are interested in hearing about these kinds of opportunities, so I’ll pass it on to them).

In the autumn, we will write an academic article about the course. More or less all of the students want to come back and help us with that, so it will be a co-authored paper. We are also hoping to put together a short video about the course.

And we will make the course content available to others, so if you are interested in running a similar course, do get in touch. We’re happy for you to use our materials as long as you attribute it to Kingston & St George’s University. The more people with learning disabilities are trained in research, the better.

But really, what we should do is run this course again. And again.

There is clearly a need out there. All I need is someone to fund it. (We don’t want people with learning disabilities, who are usually on benefits or low incomes, to have to pay for such a course.)

I’d also love to expand. These 8 weeks have shown us that people with mild and moderate learning disabilities really can be taught research skills, and that they are keen. We could only scratch the surface on this course. For those who discover that they really like research, it would be brilliant if we could run a longer, more in-depth course that would equip them to be great researchers. They could do it.

It has made me even more excited about possibilities for working with co-researchers in the future.

I have no research funding at the moment (as I said, I’ve failed spectacularly in recent years, with most of our grant applications turned down), so all I can do is dream… If only I could let funders understand that including co-researchers will make for the most brilliant research.

These students are not stupid. They really can learn, and they did. It’s just that they had never had an opportunity like this before, to learn complex skills in a serious but accessible way. They are rightly proud of their success, and we congratulate them.

I hope Richard’s headmaster, if he is still alive, reads my blog posts. I think he will find that his hypothesis was wrong.

Richard, if you are reading this: It wasn’t you who couldn’t be taught. It was the headmaster who couldn’t teach you.

Great to see the work you are doing. Makes a lot of sense to be involving people with intellectual disabilities in research opportunities and this is something I hope to do.

Reading this and watching the You-tube footage I find it truly inspiring. I hope that we can find ways to help fund the next step!

Pingback: Jargon busting |

Pingback: And the winner is… KINGSTON UNIVERSITY! |